Newsletter May 18, 2023

Gun Violence is an Assault on Community Life

There has not been a single week in the United States this year without a mass shooting. In only four and a half months, over 226 mass shootings have occurred. Each attack is uniquely horrific. Both the motives of the shooters and the fates of the victims vary in each attack. What they have in common is the human wreckage they leave behind. Mass shootings destroy individual lives, families, and communities.

That gun violence is uniquely destructive to American community life is not a new idea, but one that is seldom considered as we tally the mounting costs of inaction. In The Atlantic, Tom Nichols laments the loss of solidarity that comes from sharing and enjoying public places:

In the first few weeks after the 9/11 attacks, I traveled to London and New York. That’s when I realized that the terrorists had succeeded in making an ordinary citizen—me—think about terrorism constantly. I wondered, on my first trips back to those cities and during almost every visit to any metropolis for a few more years: Am I here on the wrong day? Is this the site of the next attack? The terrorists had, for a time, taken away my complacency and my ability to enjoy a simple stroll in a big city. Americans now have to feel this way all the time, in their own country, at almost any mass gathering, in even the quiet towns and suburbs that people once thought of as relatively immune to such terrifying events.

The worst mass shootings have nearly all occurred in public places—schools, churches, concert venues, and grocery stores—gathering spots for Americans to spend time with their friends, neighbors, and an abundance of strangers. Americans visit these places to learn, socialize, share experiences, or simply go about the acts of ordinary living. They have become so common that the federal government launched a website, ready.gov/public-spaces, to provide people with instructions on what to do before, during, and after a mass shooting.

Why Community Spaces Matter

Sociologists have been aware of the social benefits of “third places,” for quite some time. The term was coined by Ray Oldenburg more than 30 years ago. These informal gathering places may be even more important today as participation in many civic organizations and places of worship has declined. My own research has found that even living near various types of “neighborhood amenities,” such as coffee shops, bars, public parks, libraries, and gyms, provides considerable benefits. As I wrote with my colleague, Ryan Streeter:

Americans who live in communities with a rich array of neighborhood amenities are twice as likely to talk daily with their neighbors as those whose neighborhoods have few amenities. More important, given widespread interest in the topic of loneliness in America, people living in amenity-rich communities are much less likely to feel isolated from others, regardless of whether they live in large cities, suburbs, or small towns. Fifty-five percent of Americans living in low-amenity suburbs report a high degree of social isolation, while fewer than one-third of suburbanites in amenity-dense neighborhoods report feeling so isolated.

We also found that Americans with more access to these types of spaces had far higher levels of trust in their neighbors. This is key. A vibrant civic life builds social trust just as much as it is built by it.

Trust in America is in such short supply. Fears about gun violence make it worse. The ubiquity of these horrific events make it nearly impossible not to imagine violence occurring nearly anywhere we might go. In an appearance on Fox News, Alex Coker, a television host and former police officer, quoted General James Mattis in suggesting that Americans should, “be polite and professional, but plan to kill everyone you meet.” This is the same advice Mattis gave to US troops serving in combat zones.

This is exactly the problem. News stories have recently reported incidents of Americans turning on their neighbors—shooting with little or no provocation at the people living next door. Our problem is not simply that Americans are spending less time with their neighbors, but that too many people are angry, anxious, and armed.

School Shootings

More than anyone else, young people’s lives have been transformed by gun violence. An analysis by the Washington Post found that more than 352,000 students have “experienced gun violence at school” since Columbine. Even for those who have not, lockdown drills are now just part of the average school experience for many students. During the 2017-2018 school year, more than 4 million students participated in lockdown drills. Students no longer feel safe around their classmates. A 2018 Pew survey found that most teens now report being worried about a shooting occurring at their school. This feeling was especially acute among girls—64 percent say they worry about this happening. It’s certainly plausible that these fears have grown in the years since.

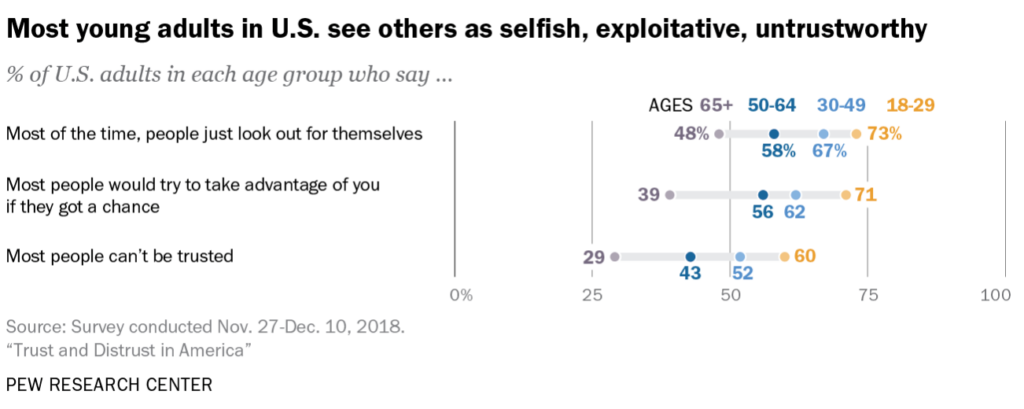

The rise in school shootings may have an especially potent effect on young people. A 2019 Pew Research Center report found that sixty percent of young adults believe that “most people can’t be trusted” and that 71 percent said, “most people would try to take advantage of you if they got a chance.” This outcome is both tragic and entirely predictable.

Gun violence often brings communities together to share feelings of grief and loss. But after the vigils are over and the protesters disperse, we are left with searing emptiness. Mass shootings change the way we think about our communities and the people in them. We feel less trusting and more fearful of each other—everyone becomes a potential threat. These attacks separate us from the people and places that provide a sense of belonging and togetherness. Mass shootings are not solely responsible for the erosion of public trust, but they remain a huge hurdle to building it back. We cannot reinvigorate community life and rebuild social trust in America without addressing the scourge of gun violence.