Newsletter October 16, 2025

Is America’s Religious Decline Responsible for Falling Birthrates?

Americans are having fewer children. A new government report found that the birth rate in the United States hit an all-time low in 2024. Whether this constitutes a crisis may depend on what you believe is causing it. Is it the inevitable result of expanding economic opportunities for women? Improved access to and education about birth control? Or is it the result of a more individualistic culture that prioritizes professional accomplishment and individual achievement?

Declining fertility rates are probably not attributable to a single cause, but in the United States, there is a strong connection to one of the defining cultural trends of the 21st century—the collapse of religious participation. In the U.S., falling birth rates have accompanied a dramatic decline in formal religious participation. Over the last 20 years, the percentage of Americans attending worship services weekly fell from 42 percent to 30 percent, according to a recent Gallup report. These trends have transformed adolescent experiences and their exposure to religious values. Pew’s 2024 Religious Landscape Study found that more than two-thirds (68 percent) of Americans now in their mid-70s or older attended services at least weekly during their childhood compared with less than half (48 percent) of those currently in their early 20s. The generational gap in formal religious education is even wider.

Pew’s landmark study also found a notable fertility gap between religiously affiliated and unaffiliated Americans. Christian Americans between the ages of 40 and 59 have an average of 2.2 children compared to 1.8 among the unaffiliated. But more importantly, it’s the decline in fertility rates that distinguishes the two groups. This decline has been more pronounced among less religious Americans—suggesting a widening gap. Our own research finds a dramatic difference in the preferences of religious and nonreligious Americans who currently do not have children. Religious Americans under age 40 without children are nearly twice as likely to say they want to have children someday as those who are not religious (62 percent vs. 32 percent).

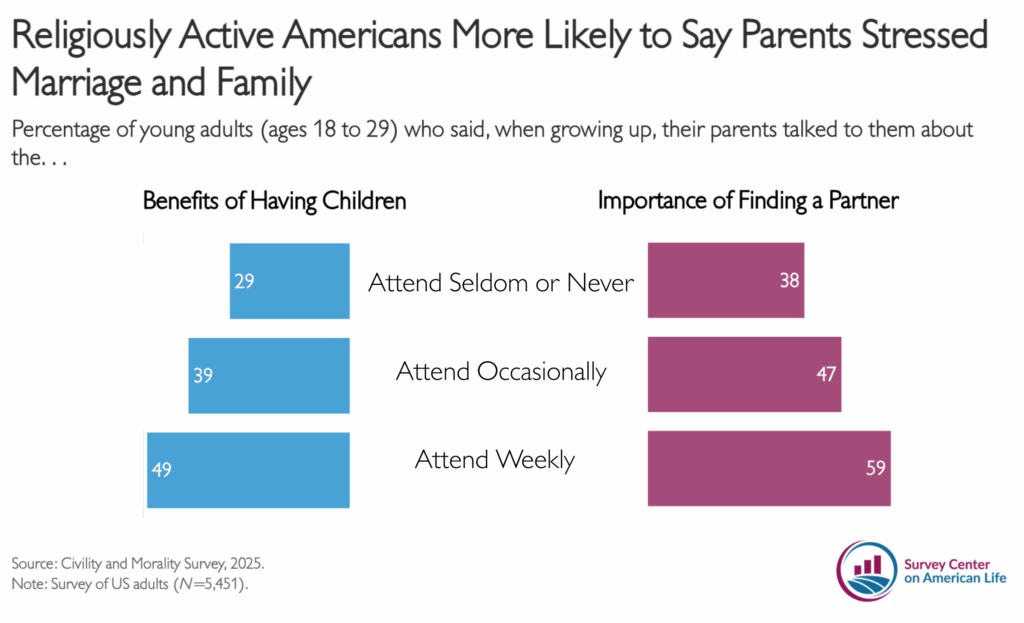

The reason religious people have more children than their nonreligious peers is not especially difficult to discern—they tend to be embedded in social contexts that prioritize marriage and parenthood. Young adults raised in religious households are more likely to report that their parents stressed the importance of marriage. Fifty-nine percent of young adults who attend religious services weekly say their parents talked at least occasionally about the importance of finding a partner or getting married. Only 38 percent of young adults who seldom or never attend religious services had the same experience.

There is a similar gap when it comes to starting a family. Nearly half (49 percent) of young adults attending services regularly heard from their parents about the benefits of having children. In contrast, fewer than three in ten (29 percent) young adults who seldom or never attend services report that their parents talked with them about the value of starting a family of their own.

Young adults today are far more likely to hear from their parents about the importance of getting an education or becoming financially independent than about marriage and starting a family. This past summer, we conducted focus groups in Raleigh, North Carolina, focused on dating and relationships. Few of the participants, in their 20s and early 30s, said their parents discussed the importance of starting a family. One young woman noted that it was her grandparents who were most likely to bring it up: “I tend to hear that more from my grandparents, because I think they’re a little bit more stuck in, you know, from when they were growing up. And my parents have never put pressure on me to find anyone or to get my family started or anything.” Hearing these types of messages regularly from people you trust matters. Roughly two-thirds (66 percent) of Americans who said their parents often talked about the benefits of having children said they want children of their own. In contrast, only 34 percent of those who said their parents never discussed these benefits said they want to start their own family.

A Wrinkle in the Gender Gap

Last year, the Pew Research Center made waves when it found that it was young men, rather than women, who were most keen on starting families. Fifty-seven percent of young men reported they wanted to become fathers someday, while less than half (45 percent) of young women said they were interested in becoming mothers. This finding is consistent with other polling as well. Not only are young men more certain in their desire to start a family, but they also express more interest than young women in having larger families. Gallup found that just over half (51 percent) of men under 50 said the ideal number of children to have is three or more. Only 36 percent of women under 50 said the same.

The hesitancy and ambivalence many young women feel about having children led to a wave of online abuse, with critics accusing women who did not want children of being selfish and miserable people. Before he became vice-president, JD Vance made an uncharitable comment about women who choose not to become mothers. In an interview with Tucker Carlson, Vance said the Democratic Party is being run by “a bunch of childless cat ladies who are miserable at their own lives and the choices that they’ve made, and so they want to make the rest of the country miserable, too.”

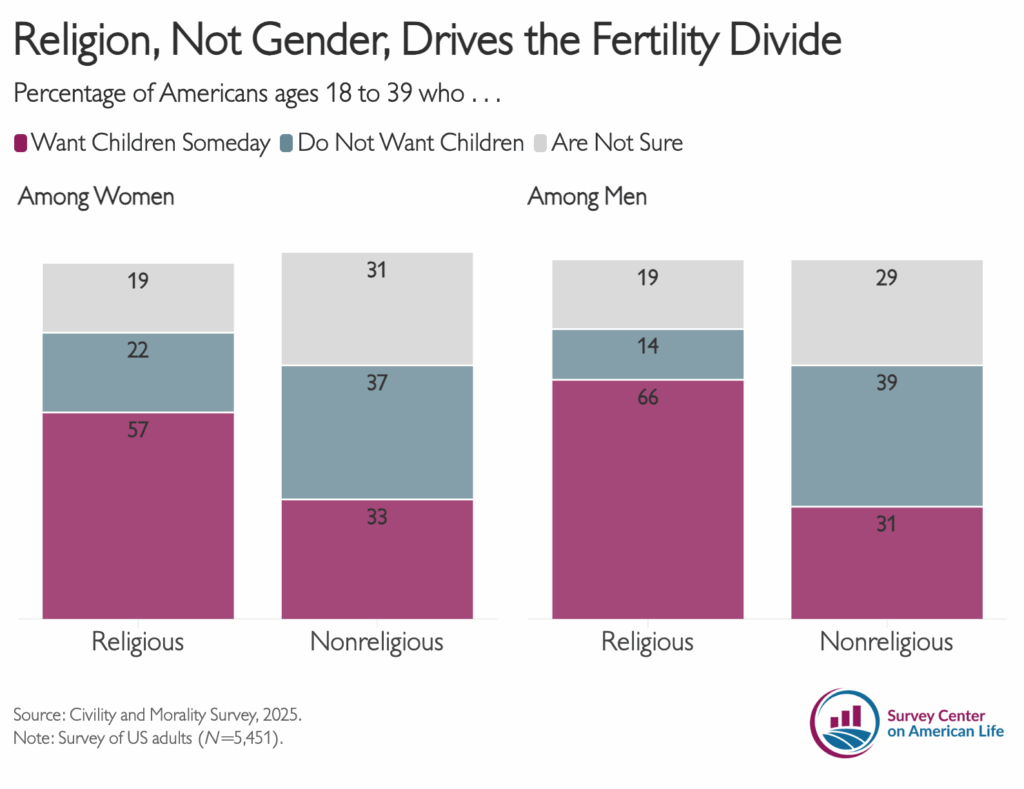

While childless women are more often criticized for their choices, many men appear similarly hesitant to start families. Secular men and women under age 40 have nearly identical preferences when it comes to parenthood. About one in three nonreligious women (33 percent) and men (31 percent) report that they want to have children someday. The gender gap only emerges among religious Americans. A majority (57 percent) of religious women say they want to have children at some point in their lives, compared to nearly two-thirds (66 percent) of religious men.1

Despite headlines suggesting (or celebrating) a national religious reawakening, there’s little evidence of a widespread return to religion. After decades of decline, Pew found that rates of religious affiliation have mostly stabilized, while rates of worship attendance remain at historic lows. This suggests that, at least for now, it’s unlikely that nonreligious singles are recommitting to religion.

Even if young Americans went streaming back to church, I’m not convinced that fertility rates would necessarily rebound. For one, fertility rates are declining across the globe, even in places that had fairly low rates of religious participation to begin with. Countries with more religious populations tend to have higher birthrates, but in many of the most religious countries, women have limited access to birth control and economic freedom. At this point, religion alone does not seem like an especially effective remedy to the country’s plunging birthrates.

For nonreligious singles, the hesitancy to start a family may stem less from a lack of faith in a higher power and more from a pervasive sense of cynicism and mistrust. Young nonreligious Americans tend to report higher rates of anxiety, greater pessimism about politics, and are more worried about the future. There are few feelings less conducive to wanting to start a family than a sense of despair. In our own research, singles without children who reported being very or completely happy with their lives were much more likely to want children than those who were unhappy (59 percent vs. 32 percent). What’s interesting about this finding is that there are so many stories of young singles or couples who are so satisfied with their childless lives that they don’t want to blow it up by having children. But in actuality, it’s the happiest people who are most committed to becoming parents.

A society that does a better job of instilling young people with a sense of hopefulness about the future will better enable them to make forward-looking decisions. Bringing children into the world is a radical act of hope. It’s a bet on the future and on ourselves. It’s also a collective enterprise. But so many of our most critical social and civic institutions—the family, churches and places of worship, and schools—focus more on meeting individual needs rather than fostering a sense of collective obligation. Churches and places of worship can help foster a culture that values children and families, but they can’t do it alone.

¹ Notably, the age, marital status, and educational background between religious and secular Americans under 40 is roughly similar, meaning that the demographic attributes are not responsible for the observed differences between them.

Read More on American Storylines