Newsletter November 27, 2025

Much Ado About Marriage

Happy Thanksgiving! If you enjoy this work, please share it with family members who you believe would value it.

Part of what I like about writing Storylines every other week is that I don’t feel pressure to have an immediate response to each new poll result or breaking news event. A bimonthly publishing schedule means I’ll almost never be the first off the mark. As a result, it encourages me towards a less reactive and potentially more thoughtful type of engagement. This schedule challenges me to offer something more than simply saying, “woah, this is news.”

This is one of those cases.

On November 14th, the Pew Research Center published a startling new analysis of Monitoring the Future data, which revealed a shift in attitudes on marriage. Although the post included a few different findings, a slate of news stories quickly converged on the drop in marriage interest among teen girls. The attention was warranted––it was a dramatic decline. In 1993, 83 percent of 12th grade girls said they wanted to get married someday; this dropped to 61 percent 30 years later. The boys barely budged, maintaining nearly identical views over the same three decades.

But the Pew analysis was more confirmatory than revelatory. There have been plenty of prior indications that young women have been rethinking their personal priorities when it comes to marriage and children:

- In a previous post titled “Is Marriage Better for Men,” I looked at why more women believed that men benefited from marriage in ways women did not.

- We found that most single women believed they are happier than married women. Single men did not share this view about themselves.

- In early 2024, Pew published research showing that young women had more reservations about having children than young men. Only 45 percent of young women said they wanted to become parents one day.

- A post-election poll from CBS News found that for young female Harris voters, having children was at the bottom of the list for their life priorities. It was the single highest priority for Trump-voting young men.

The Wall Street Journal published an entire article documenting this phenomenon titled “American Women Are Giving Up on Marriage.” The piece cited experts and polling data––including the eye-opening statistics that the share of women who said marriage was NOT important for a fulfilling life increased from 31 percent to 48 percent between 2019 and 2023.

It’s not entirely a mystery as to why this is happening. Earlier this year, I was down in Raleigh, NC, conducting focus groups among single men and women in their 20s and early 30s. To start off our conversation, I asked participants to raise their hands if their parents had ever talked with them about the importance of getting a good education and pursuing a rewarding career. Every single hand shot up. The response was identical in both the male and female groups. I then asked whether their families had stressed the importance of finding a partner or starting a family. No one raised their hand. A few of the young women said their grandparents had talked to them about the importance of finding a partner and getting married, but not their parents.

The focus group responses are certainly consistent with national polling. We found that few singles—men and women—report feeling any pressure from their families or from society to get married. Freya India, who writes the Substack newsletter GIRLS, recently said this was her experience as well. “In my world it’s the opposite: the young woman who settles down has always been seen as wasting her potential; the single, childfree, even divorced woman is strong, wise, knows her worth.” If girls were once subject to considerable cultural and familial pressure to lock down a partner, many no longer are.

It’s not simply the absence of pro-marriage messages or parental encouragement. Social media has been flooded with posts arguing that marriage is an institution inherently harmful to women. The TikTok posts below are a fairly representative sampling:

“It’s been shown that marriage isn’t actually good for women. Women who are single do better than men. Also having children isn’t actually ‘good’ for women. We have the wage gap, the motherhood penalty, and the fact that having children can put women at a higher risk of financial troubles in the future. Living with men, marrying men, and having children doesn’t “benefit women” in the same way it does men.” –– Paige Connell

“I believe that, as a woman, you should avoid getting married. You should avoid having children. I think if you’re even remotely on the fence, you need to avoid it. Marriage benefits men and having children benefits the patriarchy. … As a general concept, I think marriage represents the enslavement of women. ” –– MJ Gray

Many of these posts assert that the happiest people are married men and single women––while married women are miserable. (Surveys consistently show this to be untrue.) Even if plenty of single women do not believe that marriage is a patriarchal institution, the implication is that married men––rather than contributing to their partner’s happiness––siphon it from them.

Ephemeral Unions

Could the growing reluctance young women feel about marriage reflect a dearth of good partners? After all, single women offer this explanation far more often than single men for why they are uncoupled. Except that the pessimism about marriage extends beyond the lack of suitable candidates. One of the most troubling signs from the Pew analysis is not that young women are approaching marriage with greater circumspection, but that they are less confident that their own marriages would last. Only about half of 12th graders said that if they did get married, they would be “very likely” to stay married to the same person for life. This is a drop from 1993, when roughly six in ten 12th graders believed their marriages would go the distance. But it’s the gender divide that is most revealing. The growing pessimism about marriage is almost entirely happening among girls—boys demonstrate no real shift. Sixty percent of 12th grade girls in 1993 said they believed that they would remain married to the same person; that’s now fallen to less than half. This shift in attitudes is even more notable given that the divorce rate has fallen significantly over the past few decades.

What’s more, it’s not as if parental divorce has much bearing on the marriage rates of their children. Americans with divorced parents get married at roughly similar rates to those whose parents remained married throughout their childhood. Current singles report roughly similar preferences regardless of their parents’ marital circumstances as well.

The Problematic Pursuit of Happiness

A couple weeks ago, I was on a panel at the Brookings Institution to discuss the newly released American Family Survey, a project of Brigham Young University (BYU). One of the survey’s notable results is that fewer people believe that society is better off when people get married. Marriage is increasingly viewed as an individual endeavor, and it is deemed ‘good’ only insofar as it produces individual––rather than social––goods.

Most successful social arrangements are not exclusively designed to maximize personal fulfillment—they build trust, establish mutual responsibility, and provide a sense of belonging and security. They also force us to focus outwardly. Being obliged to think about someone else’s needs is one of the most critical benefits of marriage. It’s what makes the institution formative; we respond and adapt to another person, and in doing so, become better versions of ourselves. It also leads to happiness. The Happiness Paradox suggests that a singular preoccupation with personal fulfillment makes us miserable.

In the context of relationships, selfless people are often portrayed as victims or suckers. But spend time with people who have dedicated their lives to others, and you’ll find some of the most contented people on the planet. The data backs this up. In our research, Americans who volunteer in their neighborhoods, donate to charity, and regularly engage in acts of service report greater feelings of personal life satisfaction than those who do not.

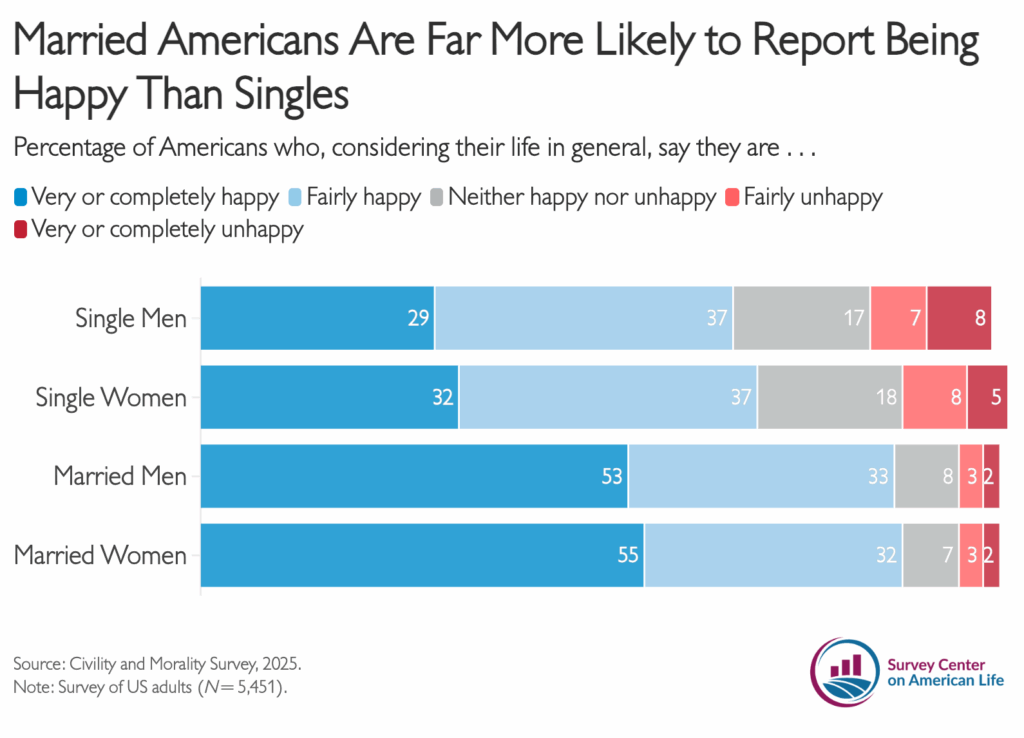

Even if personal happiness is the goal, remaining single is hardly any guarantee of well-being. In fact, research shows that compared to singles, married people report higher rates of personal satisfaction and happiness (at least as best we can measure these things on surveys). This is a pattern that holds regardless of age, race and ethnicity, educational status, and religious affiliation. A 2025 survey found that married people are leading happier lives on average than those who are single. And it’s not particularly close; 86 percent of married men and 87 percent of married women are happy with their lives compared to 66 percent of single men and 69 percent of single women.

That does not mean you are destined to be miserable if you never settle down. Instead, it suggests that the wealth of social, financial, and emotional benefits of marriage typically far outweigh whatever costs it imposes.

I don’t believe that the current doubts expressed about marriage reflect the public’s true preferences. Our personal decisions are not simply a reflection of our innermost desires but are strongly influenced by our social environment. (If this idea sounds familiar, I wrote about it very recently in the context of divorce.) When our social incentives change, so does our behavior. For example, in the same Raleigh focus groups, we asked participants to tell us what their ideal life looks like right now. Few of these young singles mentioned that marriage and family were important. We then asked them to tell us what their ideal life would be 30 years from now. Incredibly, many said that being surrounded by loving family members and grandkids was how they saw themselves living their best lives in the future. The findings suggest that young adults are aware of the personal benefits of family later in life but fail to understand how this future result requires present-day investments.

In The Good Life, Robert Waldinger and Marc Schulz analyze more than eighty years of data on human health and wellbeing to conclude that strong personal relationships, especially intimate relationships, are the key to a meaningful and fulfilling existence. Ironically, they note that many of us fail to recognize this fundamental fact. “We seem particularly bad at forecasting the benefits of relationships. A big part of this is the obvious fact that relationships can be messy and unpredictable. This messiness is some of what prompts many of us to prefer being alone. It’s not just that we are seeking solitude; it’s that we want to avoid the potential mess of connecting with others. But we overestimate that mess and underestimate the beneficial effects of human connection.”

If intuition is not a helpful guide when it comes to understanding the value of marriage, then it comes down to modeling and messaging. The people benefiting from marriage are best positioned to speak to the benefits it confers and the sacrifices it requires. And these things are often one in the same. We derive meaning and purpose from our relationships not from their outputs but from their inputs. In the end, people should be free to choose the lives they want, but we should all be more honest about the tradeoffs these choices entail.

Read More on American Storylines