Newsletter October 19, 2023

Are Generational Labels Meaningless?

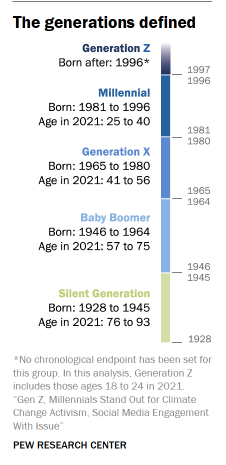

In popular culture, generational labels, such as Millennial, Baby Boomer, Generation Z, and that other one, have become ubiquitous. But there is a growing movement to do away with these categories out of concerns that they exacerbate generational tensions and misinform the public. In the Washington Post, Sociologist Philip Cohen wrote, “Worse than irrelevant, such baseless categories drive people toward stereotyping and rash character judgment.” He went further, publishing an open letter to the Pew Research Center requesting they cease using these labels. More than 330 sociologists and demographers agree with him.

I respectfully do not.

Generational Differences Are Becoming More Important

I would argue that generational categories—imperfectly defined though they may be—are more meaningful than ever. In her recent book, Generations, Jean Twenge makes the convincing case that technology usage is a critical dividing line between generations. Twenge argues that “technological change isn’t just about stuff, it’s about how we live, which influences how we think feel and behave.” Teens in the era of smartphones and social media have qualitatively different experiences than those who came of age before these technologies. Evidence suggests that young people today are spending less time with their friends in person, are reporting more frequent feelings of loneliness, and are less trusting.

The pace of technological change and its capacity to reshape nearly every aspect of our lives will further exacerbate generational divisions. The Internet revolutionized the way people access information and communicate with each other, while smartphones transformed access to information and to each other. Recent advances in artificial intelligence, autonomous vehicles, and computer speech recognition also promise to dramatically reshape how we live. These developments will only dig deeper divisions between the generations born before the adoption of these technologies and those who have only experienced life with them.

But it’s not just technological advancements increasing the relevance of generational categories. In the United States, a rapidly diversifying population is creating greater cleavages between generations. In Diversity Explosion, demographer William Frey argues that “the racial makeup of the nation’s younger population is beginning to contrast sharply with that of the older populations. Analysis of Census data shows that only about half of Gen Zers are white compared to more than eight in ten Baby Boomers when they were the same age. These demographic differences have a profound impact on politics and personal life choices. Young people today have far more diverse friendship groups than past generations, more readily embrace the value of diversity and pluralism, and are more likely to form multi-racial and multi-religious families.

For those concerned about rising intergenerational conflict, I would argue that a focus on mean memes, like “Ok Boomer,” is a distraction. Rather, as journalist Ron Brownstein argues, the widening demographic gap between generations is setting up a cultural wedge between largely white older generations and the rapidly diversifying younger cohorts.

Where To Go From Here?

The most frustrating aspect of the complaints against the use of generational labels is that critics offer no realistic path forward. What should journalists or researchers use instead of these labels? Should we use decades to define age cohorts? That doesn’t seem any less arbitrary to me.

Is it reasonable to expect everyone will just stop using generational labels? There has been an incredible amount of collective time and energy invested in researching and understanding the experiences of different generational cohorts. It’s not just news outlets that use generational categories in their reporting; the U.S. Census has embraced generational labels in its research, including the use of them in educational materials. I fail to see how dropping these labels will contribute to better public understanding.

Regardless of what you think about the appropriateness of Pew’s generational definitions, they serve an important purpose in establishing a consistent benchmark upon which other scholars, journalists, and public policy professionals can rely. I have used them in my own research. In the absence of an agreed-upon definition, individual researchers will develop their own standards for generational categories, making comparisons more difficult and confusion more likely.

I make these arguments not in defense of a particular academic specialty, but as someone who has spent a career communicating research findings to the general public. In this work, having standard definitions and well-established categories is invaluable. If some of the most reputable researchers no longer use these terms, the less reliable sort will likely take full advantage of this absence, employing less precise methods or inconsistent approaches. Abandoning generational labels without offering a suitable replacement invites chaos and confusion.

The growing relevance of generational labels is reflected in widespread public understanding of them. A 2023 survey found that more than 60 percent of Americans can correctly identify the Pew-defined generation to which they belong. The percentage is even higher among those born in the “peak years” of each generation. Meanwhile, very few labeled themselves incorrectly. But most importantly, one-third of the survey sample felt “the generation they belonged to was important to their personal identity.”

I’m not arguing that Pew’s definitions are beyond criticism. Rather, I believe generational categories are meaningful, and having a way to talk about them is critical. What’s required is a definition that is simple, consistent, and constructed using methods that are transparent.

As Jean Twenge has argued, a perfect definition is not necessary—the goal should be to acknowledge that formative experiences matter and ensure surveys account for them:

The truth is that generational labels and birth year cutoffs are merely convenient shorthand; although some generations clearly begin with a pronounced cleft from the earlier group, generations often bleed into one another. However, the arbitrary nature of generational names and spans does not negate the reality that growing up during different eras can have a profound effect.

For those who believe it would be impossible to modify generational cohorts or labels, I invite you to review the history of U.S. Census racial categories. The way the Census measures race has been continually updated and will likely undergo additional revisions in the future.

Millennial is not a personality trait, and not all Baby Boomers think alike. There is an incredible amount of diversity among any generational cohort, but this is true for any demographic characteristic. I’m sympathetic to complaints about the way these categories are covered in popular media. The solution is not to restrict the availability of reliable research, but rather to better inform and educate the reporters and columnists trafficking in snarky, reductive generational stereotypes. Social scientists, public scholars, and government researchers should work together to reform the standards and practices of generational research rather than simply throw it all away.